For generations, one of the Milwaukee’s most prestigious addresses was the St. Charles Hotel (786 N. Water St.,) a house with a long and colorful history.

Captain Upman takes command

It all began in 1844 with Captain Diedrich Upman, a Water Street tavern owner from Hanover, Germany. One of the city’s first settlers, Captain Upman watched Milwaukee grow from a small camp to a thriving Western town. He knew it could and would become something much greater in time.

The Captain’s reputation as a "jolly old German" always preceded him. After returning home from the Mexican-American War in 1848, he managed a land office in Winona, Minnesota. "He approved for an abandoned church to be converted into a saloon. This was the captain’s favorite resort when thirsty, which occurred quite frequently, and he would always say on such occasions, 'The bells are ringing; come, boys, we must go to church. It is unlawful to try cases on Sunday,'" wrote Charles Eugene Flandrau in "The History of Minnesota and Tales of the Frontier" (1900).

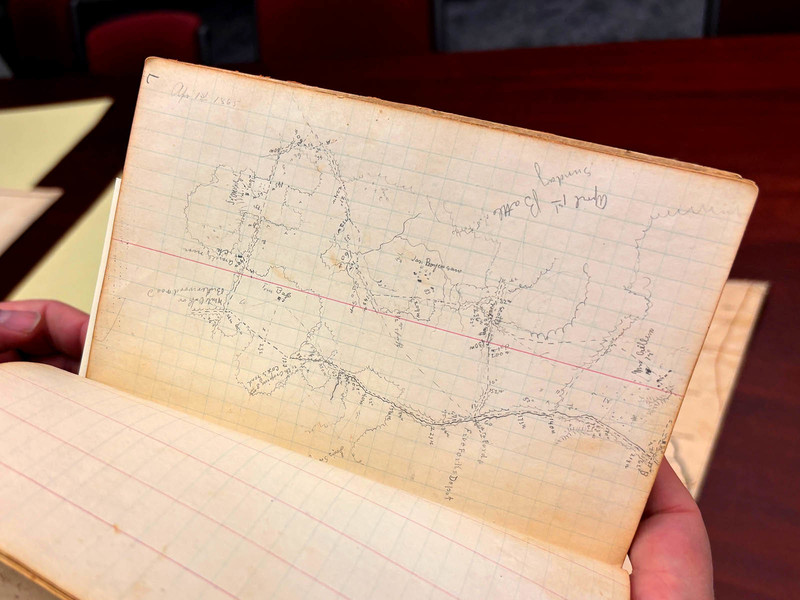

In 1859, he purchased the bankrupt Hotel Wettstein on Milwaukee’s Market Square. Only a decade earlier, he had led military recruits on nightly drills through this square, and later, onto the steamboat Louisiana and off to war. Now, Upman was leading a new mission: to build the finest hotel in Milwaukee.

His goal was to recreate the majestic St. Charles Hotel in New Orleans, after spending many happy hours there after the war. As the first large building constructed above Canal Street, the St. Charles Hotel inspired the expansion of New Orleans outside the French Quarter. Historians recognize the St. Charles Hotel for transforming a swampy wilderness into a modern central business district within a generation. The St. Charles was considered the grandest hotel in the South, and the first truly great American hotel worthy of a Presidential visit. The massive Neoclassical monument was capable of housing up to 800 guests at one time.

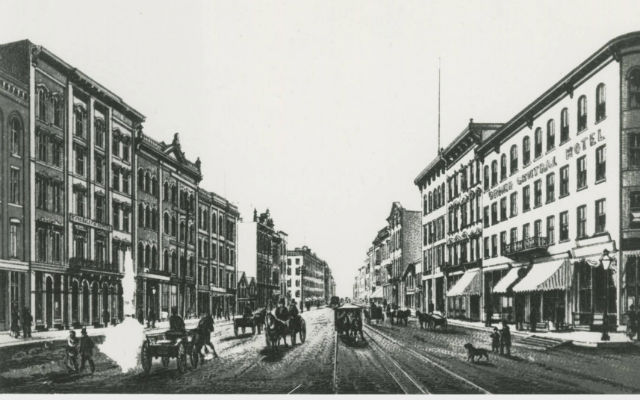

That’s a hard act to follow, but Upman was dedicated to his goals. He knew that a grand hotel could anchor Market Square and transform Milwaukee into a world class city. After a year of tireless construction, his St. Charles Hotel opened with a formal ball, generous supper and spectacular fanfare on Tuesday, June 12, 1860.

"Upman did everything in his power to contribute to the enjoyment of his guests," said the Milwaukee Sentinel. "The St. Charles has been handsomely fitted up and furnished from top to bottom. It will be kept in excellent style and cannot fail to become popular with the travelling public."

"The captain, besides being a gentlemanly and intelligent man, has traveled, and has gathered just the kind of experience to enable him to keep a worldly hotel," said the Portage City Record.

One of the hotel’s most memorable features was a first-floor lobby bar that ran the entire length of the building. Architects argued against Captain Upman’s vision, but in the end, the bar was built to last.

The St. Charles Hotel was only the beginning of Upman’s empire. In 1862, Captain Upman sold out to brothers Christian and Valentine Fernekes, who ran the operation for the next 30 years. Captain Upman moved on to open hotels in Chicago, St. Paul and Chattanooga. He died in 1884 at the age of 61, leaving behind a widow and eight children. His son, Frank Upman, would become a prominent figure in the United States hotel industry.

The heart of the German Athens

The Industrial History of Milwaukee, published in 1886, describes the St. Charles Hotel as "a large imposing brick structure, five stories in height, with a frontage of over 155 feet and a depth of 150 feet. Its halls are wide and its rooms cheerful and inviting. The cuisine of the St. Charles Hotel is perfect in every respect. Their passenger and baggage elevators render all of the floors easy of access. Bathrooms and closets, electric bells, steam laundry, barbershop, elegant billiard parlors, and bar are all attractive. One feature worthy of note is the perfect arrangement and provision made for the safety of guests in case of fire." This last note was important for travelers, as the Newhall House disaster of 1883 was still fresh in their memories – and would remain the most deadly hotel fire in U.S. history for decades.

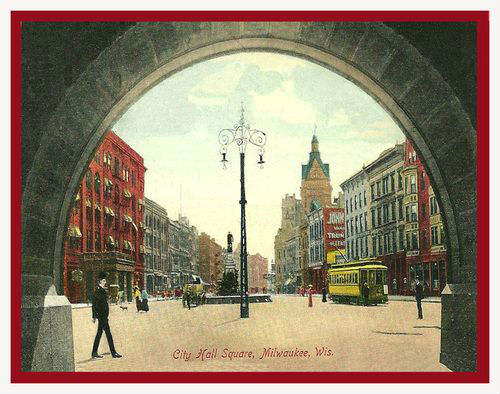

The St. Charles was among the oldest hotels in the city when it was purchased and thoroughly renovated by the Pabst family in 1895. The renewed hotel became the eastern anchor to a gorgeous, European-style City Hall Square that included the Blatz Hotel, The Pabst Theater, the Henry Bergh animal drinking fountain and the brand new Milwaukee City Hall (until 1899, the tallest building in America).

It had taken 35 years, but Upman’s vision of a world city was now achieved. Soon, the Pabst Hotel register was filled with the names of distinguished German royals, robber barons, captains of industry and politicians of every level. It was a favorite meeting place of the Old Settlers Club and the Chamber of Commerce. In 1896, the American Appraisal Company was founded in one of the hotel’s fifth floor rooms.

Franklin Matchette, agricultural scientist and president of the Nitragin Company, operated the hotel from 1904 to 1920. But by the 1920s, City Hall Square was no longer swank. Decades of coal pollution had stained the formerly elegant buildings, financial panics had delayed renovations and Milwaukee’s ornate Teutonic architecture had fallen out of fashion. The St. Charles Hotel had become more residential than commercial, with many guests renting their rooms by the month.

In 1923, the Pabsts sold the hotel and removed their family name from the cornice. The timing of this exit couldn’t have been better, because the St. Charles Hotel would soon plunge into a scandalous moral decline.

Jazz babies, gin parties and burlesque bordellos

On June 1, 1928, the St. Charles was the scene of a spectacular Prohibition raid that blew the top off this house of ill repute. At 1:30 a.m., federal agents seized gin, whiskey, grain alcohol and two highballs that guests were about to consume, and arrested three hotel employees. Two of these employees had prior liquor convictions.

As the hotel was shut down, the U.S. District Attorney reported, "We have absolute evidence that liquor was sold promiscuously at the hotel. We have evidence that booze was sold in at least 20 rooms. This is the heaviest padlock the government has ever asked for in Wisconsin."

"There appears to have been no difficulty whatsoever in getting liquor here," said Federal Judge F.A. Geiger. After all, the St. Charles Hotel was widely known as a "cutting plant" for the manufacture of illicit alcohols. It soon became popular for other reasons, as the agents reported the behavior of the "lewd chorus girls from the Gayety Theater." One agent reported that uninvited performers came into his room, made themselves at home and drank gin freely.

"You could have liquor parties in the St. Charles Hotel any night you wanted them, with chorus girls attending. All you had to do was call the desk and order a bottle. Gin was delivered immediately. Persons prominent in Milwaukee’s social circles had parties there."

C.N. Caspar, owner of the neighboring Book Emporium, was one of those prominent guests. Caspar, known for his collection of erotica and other forbidden literature, maintained a secret room on the third floor of his shop where he entertained chorus girls from the St. Charles Hotel. After Caspar’s death, local bookseller Harry W. Schwartz inspected this room and commented, "It certainly would have been an elegant little bordello."

Cocktails often led to reckless abandon. One agent accounted, "The girls came to my room for drinks wearing only kimonos, step-ins, shoes or smiles, and often turned handstands or somersaults on the floor." Of course, when cross-examined, the agent admitted that he had never asked the women to leave – nor stop their naked gymnastics.

Prohibition agents used curious language to describe the crowds at these St. Charles Hotel parties. "Bull daggers and pansy boys haunt the [St. Charles] hallways," reads one report. "Degenerates will find doors open to them here." Through these reports, the St. Charles Hotel became known as a gathering place for gays and lesbians – one of the first ever documented in Milwaukee.

The St. Charles Hotel and over $410,000 of property was padlocked and seized for one year from July 11, 1928. It was the largest hotel ever padlocked as a dry law nuisance in the United States.

For the first time, Milwaukee media began to cast a negative light on the idea of "residential hotel living." When the hotel was locked, bootleggers and beggars sat around the lobby for days comparing rates, while others conceived the idea of pitching a tent in City Hall Square. After all, it had its own "private swimming pool" (the Henry Bergh watering trough) and "one second’s jump to a streetcar line." Cabaret entertainers, speakeasy owners, gamblers and night revelers appeared to be the only residents of the St. Charles Hotel. Seventy-one permanent "guests" were ultimately thrown out of their rooms and became refugees.

One year later, the padlocks came off the St. Charles Hotel, which reopened on July 19, 1929 under the same management. Incredibly, 70 of the 71 former guests reclaimed their dust-covered rooms. But the dust never really settled for the St. Charles.

On July 26, 1930, the hotel was again under scrutiny for allowing young girls to register without chaperones or baggage. Although the hotel was later cleared of charges, a juvenile court judge accused the hotel of leading young girls into the burlesque lifestyle. The judge was most likely right.

Strange days, stranger nights

On Sept. 16, 1931, a heavy plate glass rooftop skylight fell 75 feet and crashed into the mezzanine of the St. Charles lobby. Amazingly, nobody was injured or killed. The cause of the collapse was never determined, and a series of unexplained phenomena followed. Window panes would fall out of their frames into Water Street below. Guests would wake up screaming about intruders in their rooms. A visitor woke up to find her room on fire, but when help arrived, there was not even a hint of smoke. One of the hotel’s oldest guests was found days after dying in his bed on the fourth floor, yet hotel staff claimed to have seen him coming and going.

A famous Center Street fortune-teller visited the hotel and spoke of a menacing presence that wanted everyone to leave and lock the doors behind them. Reporters mocked her séance, but not without noting that old Captain Upman might be fed up with the free-for-all speakeasy that the St. Charles had become.

After federal indictment, near-bankruptcy and a sensational divorce, manager Joseph Budar had seen and heard enough. At sunset on Oct. 8, 1931, the St. Charles Hotel went dark again. Budar assumed management of the Royal Hotel (435 W. Michigan St.) and took most of his staff and residents with him. A caravan procession ensued as guests dragged their trunks, luggage and furniture down Water and Michigan Streets to their new home.

Only five years old, the Royal Hotel was already a girl down on her luck when the Budar caravan showed up. Almost immediately, gays and lesbians began to gather at the Royal Hotel Bar and Café, taking advantage of the open, accepting atmosphere once found in St. Charles Hotel hotel rooms. Hotel management openly supported anyone arrested for morals or misconduct charges. The bar remained popular through the 1970s, when it was known as the Stud Club (1971) and Michelle’s/Club 546 (1972). The run-down hotel was finally flattened in 1974, but not before a closing party where guests received keys to their most memorable rooms as parting gifts. Some Milwaukeeans still hold these keys today. Assurant Health headquarters (501 W. Michigan St.) sits on the former footprint of the Royal Hotel.

End times

Milwaukee County briefly considered the St. Charles Hotel as an indigent home for the unemployed. But, as the new hotel owner stated in 1931, "The property is more valuable without a building on it, so we decided to wreck it."

Within a year, the St. Charles was torn down, destroying the European character of the original City Hall Square. Plans for a new building on the site were announced, but eventually cancelled. For no real reason at all, one of the city’s most visible blocks was a gravel parking lot for over 35 years.

M&I Bank purchased the land in 1947 and announced plans for a modern extension. In 1968, the skyscraper at 770 N. Water St. (now known as BMO Harris Bank) finally opened to the public. As all eyes turned to the new M&I skyscraper as a sign of progress, few noticed that the historic Blatz Hotel (built in 1872) across City Hall Square was being demolished for parking.

Joe Yule, stage actor and father of Mickey Rooney, lived at the St. Charles Hotel while performing at the Gayety Theater on 3rd and Wells. He hired Elmer Regner, later the executive producer of the Melody Top Theater, to babysit while he was working.

Shortly before his death, Joe shared his memories with the Milwaukee Journal. "I hadn’t been in town for over 20 years, so I headed straight to the St. Charles for a look see. Imagine my feeling. Torn down. Nothing left there to see. I stood at the horse trough in front of City Hall and just looked for a long time."

We know how you feel, Joe.